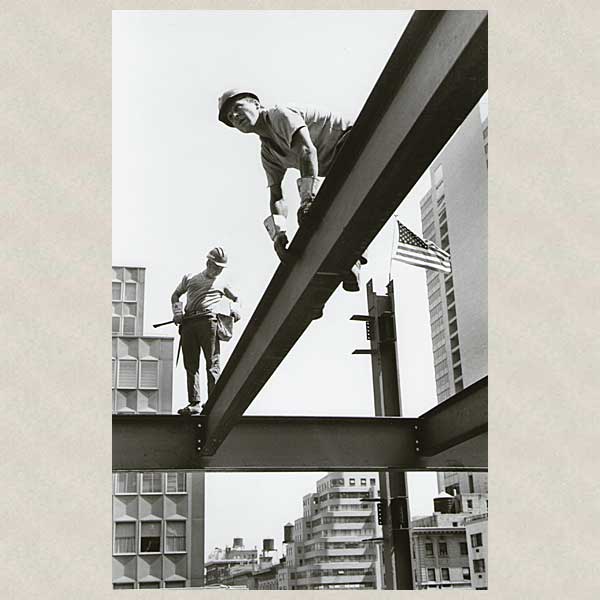

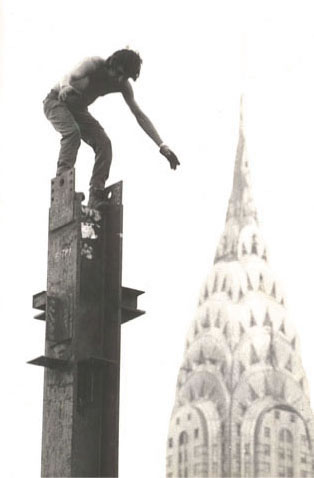

The Skywalkers blanket design (available now) was inspired by Art Deco design elements of some of New York City’s iconic skyscrapers such as the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building. It is a salute to the skilled Native American and First Nations iron workers who built some of the city’s famous landmarks, including the George Washington Bridge and the new One World Trade Center.

To see the faces of these seemingly fearless men, please visit this incredible collection of tintypes by Melissa Cacciola.

You can read the entire story below, which is a repost from Whitewolfpack.com and used with their permission. The original text of the article is written by Renee Valois. The following photographs are copyright © 2012 David Grant Noble.

For generations, Mohawk Indians have left their reservations in or near Canada to raise skyscrapers in the heart of New York City.

High atop a New York University building one bright September day, Mohawk ironworkers were just setting some steel when the head of the crew heard a big rumble to the north. Suddenly a jet roared overhead, barely 50 feet from the crane they were using to set the steel girders in place. “I looked up and I could see the rivets on the plane, I could read the serial numbers it was so low, and I thought ‘What is he doing going down Broadway?’” recalls the crew’s leader, Dick Oddo. Crew members watched in disbelief as the plane crashed into one of the towers of the World Trade Center, just 10 blocks away.

At first, Oddo says, he thought it was pilot error. He got on his cell phone to report the crash to Mike Swamp, business manager of Ironworkers Local 440, but he began to wonder. Then another jet flew by. “When the plane hit the second tower, I knew it was all planned.”

Like Oddo, most of the Mohawk crews working in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001, headed immediately to the site of the disaster. Because many of them had worked on the 110-story World Trade Center some three decades earlier, they were familiar with the buildings and hoped they could help people escape faster. Fires were raging in the towers and the ironworkers knew that steel weakens and eventually melts under extreme heat. They helped survivors escape from the threatened buildings, and when the towers came crashing down, they joined in the search for victims.

In the months that followed, many Mohawk ironworkers volunteered to help in the cleanup. There was a terrible irony in dismantling what they had helped to erect: Hundreds of Mohawks had worked on the World Trade Center from 1966 to 1974. The last girder was signed by Mohawk ironworkers, in keeping with ironworking tradition.

Walking the iron

Mohawks have been building skyscrapers for six generations. The first workers came from the Kahnawake Reservation near Montreal, where in 1886 the Canadian Pacific Railroad sought to construct a cantilever bridge across the St. Lawrence River, landing on reservation property. In exchange for use of the Mohawks’ land, the railroad and its contractor, the Dominion Bridge Co., agreed to employ tribesmen during construction.

The builders had intended to use the Indians as laborers to unload supplies, but that didn’t satisfy the Mohawks. Members of the tribe would go out on the bridge during construction every chance they got, according to an unnamed Dominion Bridge Co. official quoted in a 1949 New Yorker article by Joseph Mitchell (“The Mohawks in High Steel,” later collected in the 1960 book Apologies to the Iroquois, by Edmund Wilson). “It was quite impossible to keep them off,” the Dominion official said.

The official also claimed the Indians demonstrated no fear of heights. If they weren’t watched, he said, “they would climb up and onto the spans and walk around up there as cool and collected as the toughest of our riveters, most of whom at that period were old sailing-ship men especially picked for their experience in working aloft.”

Impressive perhaps, but Kahnawake ironworker Don Angus explains that his ancestors back then were just teenagers daring each other to climb the 150-foot structure and “walk the iron.” Company workers tried to chase them off the bridge, Angus says. “I know that for a fact. They were getting in the way.”

The Indians were especially interested in riveting, one of the most dangerous jobs in construction and, then as now, one of the highest paid. Few men wanted to do it; fewer could do it well, and in good construction years there were sometimes too few riveters to meet construction demand, according to the New Yorker article. So the company decided to train a few of the persistent Mohawks. “It turned out that putting riveting tools in their hands was like putting ham with eggs,” the Dominion official declared. “In other words, they were natural-born bridge-men.” According to company lore, 12 young men—enough for three riveting gangs—were thus trained.

After the Canadian Pacific Bridge was completed, the young Mohawk ironworkers moved on to work on the Soo Bridge, which spanned the St. Mary’s River connecting Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, and Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. Each riveting gang brought an apprentice from Kahnawake to learn the trade on the job. When the first apprentice was trained, a new one came up from the reservation, and by 1907 more than 70 skilled structural ironworkers from the reservation were working on bridges.

Then tragedy struck. American structural engineer Theodore Cooper had designed the Quebec Bridge, a cantilevered truss bridge that would extend 3,220 feet across the St. Lawrence River above Quebec City. Because the Quebec Bridge Co. was strapped for cash, the company was eager to accept his design, which specified far less steel than was typical for a bridge of that size.

View our full range of blankets here

Photos Copyright © 2012 David Grant Noble